Flight of the Eagle

Flight of the Eagle <=*S======<>+O+<>======<^>====<<<+O+>>>====<^>======<>+O+<>======S*=>

Native Pride Wisdom

History and Stories from Native Americans

Book i

<=*S=======<>+O+<>=====<^>====<<<+O+>>>====<^>=====<>+O+<>=======S*=>

Profiles From

American Indian History

<=*S=======<>+O+<>=====<^>====<<<+O+>>>====<^>=====<>+O+<>=======S*=>

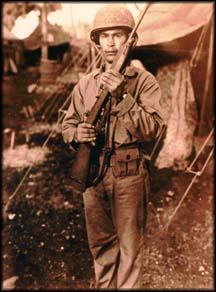

Dear Readers... Today's profile is highlighting the Navajo Code Talkers of WW2. This is a term paper my daughter wrote for her 8th grade social studies class. Sometimes we might feel that much of our culture and heritage has been lost, but when we see the youth of our day learning, and then sharing that knowledge, our hearts should be filled with pride.

How the Navajo Language

Helped Win WW2

On the island of Saipan the troops were advancing in on the Japanese. When they got to the camp there was no one there. They were then starting to be attacked by their own bombers. The Japanese had sent a message to the U.S. to bomb the area. The men quickly radioed for them to stop. The bombers thought they were being tricked and would not stop. When the Navajo code was used, they stopped bombing immediately. The code was used to save lives on this day and many others. This code was one of the only unbroken codes in World War II (Aaseng 1-3). The Navajos would help win the war for the U.S. and its allies.

The early Navajos settled in Arizona, New Mexico, and southern Utah. After many years the white men forced them to move to Fort Sumner. Most died there or on the way. This was called the Long Walk. The ones who made it were made to live life as if they were in a concentration camp (Aaseng 6-7). In 1868 they were allowed to move home if they promised not to fight against the U.S., Mexico, or other Native Americans (Aaseng 9). They were able to keep their original land at the reservation because it was dry and not good for planting. The reservation was over 25,000 square miles; larger than West Virginia (Aaseng 23). Thousands of Navajo children had no chance for education. Of the Navajo of military age three out of five didn't speak English and nine out of ten were classified as illiterate (Aaseng 26). They stayed close to rituals and governed themselves according to tradition. They never forgot the Long Walk and didn't trust the European descendants or their government.

The Navajo language is very different. Every syllable has a different meaning. The four tones are high, low, rising, and falling. The language was never written. When new things were introduced to the culture they would make their own word for it instead of adopting the English word. There can be more than one word for some things. For example, the word “dropped” is different depending on what was dropped. All of these factors made Navajo a difficult language (Aaseng 18-21).

When the U.S. entered WW2 they needed a code. Philip Johnston, a common U.S. citizen, thought of using the Navajo language. In his youth he was friends with Navajo children. Navajos were told in school not to speak their language, but most of the soldiers owe their lives to the disobedience. He contacted Lieutenant Colonel James Jones and they met in February 1942 (Aaseng 19). The project was then put into affect. The plan was downscaled drastically, so if it didn't work there wouldn't be a huge loss.

In April, 1942, recruiters were sent to reservations to find candidates (Aaseng 22). At first, Navajos didn't want to join because the recruits couldn't tell them much about the program. Then they were able to get more information, Navajos were eager to join the program. Some lied about their age or tried to gain weight to meet requirements (Aaseng 26-27). Thirty people were chosen to go to a training camp near San Diego (Aaseng 27). Life was very different outside of the reservation. They had to adapt to a new culture and food. Their symbolic long hair was cut to a Marine-type haircut (Bixler 64). They were then sent to Camp Pendleton to learn techniques of communicating messages. Military discipline was a shock, but they were able to do every grueling task set before them. They were taught to use heavy war radios and other methods of communication. The most important thing they had to do was make a code. They were given four rules to develop the code. It had to be descriptive or creative, relatively short, a word that couldn't be confused with others, and have a logical connection to what it stood for. The 211 terms most used were to be given a code name and had to be memorized (Aaseng 30). Places were spelled out but not with English letters. They took an English word that started with that letter and translated that word into Navajo. At the end of training they were put into a real war situation while other officers tried to break the code. They were able to encode, transmit, and decode a three line English message in twenty seconds (Molnar NP). None of the English-speaking soldiers were able to decode it, so the code was used in the war.

Philip Johnston was accepted to the Marines and put in charge of the code talker program. Sometimes the code was thought to be Japanese and sent U.S. troops into panic. The Navajos also looked like the Japanese, which was very dangerous for them during the war. One Navajo was captured by his fellow Marines, so no message was able to get through. Some Navajos were used to carry messages across enemy lines, and some died. After a while, bodyguards were assigned to the code talkers so they would not be captured by the U.S. troops that thought they were Japanese.

With new things being invented the 211 words were not enough. The code was then almost doubled to fit the need. They found alternate words to use for letters along with the old ones. In December, 1942, code talkers were requested in Guadalcanal, which the Japanese were later forced to abandon (Aaseng 49). On February 19, 1945, with the help of code talkers, the U. S. led an attack on Iwo Jima (Aaseng 90). When they reached the beaches, the Japanese opened fire. The troops jumped into holes on the beach to escape the fire. The Japanese had made it so the holes were fired into, too. The code talkers were able to tell the troops where the Japanese were hidden and to where the submarines were aiming. During a 48-hour period they sent and received more than 800 messages (Aaseng 96). By the end of the first week the American flag was planted in a mountaintop and the island was officially captured on March 16 (Aaseng 97).

After the war, the Navajo soldiers went home to the reservations. Their great risk in the WW2 had no effect on their relations with the whites. They still had inadequate education and in some states they couldn't vote. This was a great contrast to how they were treated at home. On the reservation they were greatly respected, while others thought they were not (MacDonald 74). In 1971, President Nixon awarded the code talkers a certificate of thanks. They were thought of as heroes (Bial 104). More than 400 code talkers were used in the Marines in the Pacific (Aaseng 3). With the Long Walk behind them about 3,600 Navajos joined the armed forces in WW2 (Aaseng 10). After all that the government did to them they still fought to protect the U.S.

<=*S=======<>+O+<>=====<^>====<<<+O+>>>====<^>=====<>+O+<>=======S*=>

(??-1692)

A religious leader from San Juan Pueblo in present-day New Mexico, Popé organized and led the most successful Indian uprising in the history of the American West.

Very little is known of Popé's life. He was apparently a native of San Juan Pueblo, but moved to the nearby pueblo of Taos in the 1670's. Provoked by a Spanish crackdown on native religious practices in 1675, Popé soon began conferring with other disaffected Pueblo leaders, some Apache with ties to the Pueblos, and nearby villages, about the possibility of large-scale revolt against the Spanish. He offered a millenarian vision to the Pueblos, stressing the complete expulsion of Spanish military and religious authority, the elimination of Christian and Spanish cultural practices, and the return of Pueblo deities. Despite his cultural militance, Popé seems to have been deeply influenced by Christian cosmology, for his emphasis on the return of three Pueblo deities bears a striking resemblance to the Christian trinity.

Popé launched his revolt early in August 1680. He achieved stunning success, due to the Pueblos' vastly superior numbers -- more than 8,000 warriors against fewer than 200 arms-bearing colonists -- and to the high degree of coordination he had achieved. Despite language differences and distance, the Pueblos attacked everywhere at once, killing 21 Franciscan friars and more than 400 Spanish colonists. Those Spanish who survived this initial onslaught fled to the Governor's Palace in Santa Fe, where Popé's warriors surrounded them. In late August, they made a desperate attempt to break the Indians' siege and were lucky to escape to El Paso.

Having driven the Spanish from New Mexico, Popé tried to eradicate every possible vestige of their culture. He ordered the destruction of Christian objects and churches, punished the speaking of Spanish and the use of Spanish surnames, and argued against using Spanish tools such as the plow. In his style of leadership and exercise of personal power, however, Popé seems to have retained an element of Spanish authoritarianism which alienated many and contributed to the breakup of the Pueblo alliance.

Less than a year after Popé's death in 1692, troops under Diego de Vargas reconquered New Mexico for Spain. But reconquest did not mean a return to the days before the uprising. Popé's revolt had permanently weakened the political power of the Franciscans, whose missionary efforts had been the focus of Spanish interest in the region. Now Spain was more interested in New Mexico as a barrier between the French and Mexico's northern provinces. Accordingly, the Pueblos were now given greater latitude for their own religious practices, and fewer demands for food and labor were placed upon them. The Spanish even armed the Pueblos to defend their own villages and acknowledged their rightful ownership of village lands. In short, the post-rebellion political system in New Mexico can be seen as a Pueblo-Spanish alliance, particularly in respect to their common enemies, the Apache, Navajo, Ute and Comanche raiders.

Given his nativistic radicalism, Popé could never have welcomed such an alliance between the Pueblos and the Spanish, yet by making this alliance possible, he created the conditions for a new culture to emerge in the American Southwest, a blend of Indian and European influences which retains its distinctive character even today.

<=*S=======<>+O+<>=====<^>====<<<+O+>>>====<^>=====<>+O+<>=======S*=>

(c. 1790-1812 or 1884)

A near-legendary figure in the history of the American West for her

indispensible role on the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Sacagawea has become an enigma for historians seeking to trace her later life.

The daughter of a Shoshone chief, Sacagawea was kidnapped by the Hidatsa when she was about ten years old and taken back to their village on the upper Missouri. There, she and another captive girl were purchased and wed by Toussaint Charbonneau, a French Canadian trapper.

When Lewis and Clark engaged Charbonneau as an interpreter for their expedition in 1804, it was with the understanding that Sacagawea would also accompany them. Aside from her value as an interpreter, they expected her mere presence to speak well of them to Indians they would encounter along the way. As Clark noted in his journal, "a woman with a party of men is a token of peace."

Eight weeks before Lewis and Clark set out from the upper Missouri, a second token of peace was added to the expedition when Sacagawea gave birth to her first child, a son named Jean Baptiste Charbonneau but called Pomp or Pompey by Clark. Sacagawea carried her infant on a cradleboard as the "Corps of Discovery" headed upriver in April, 1805.

Four months later, when the expedition had reached the navigable limits of the Missouri, Lewis set out to make contact with a Shoshone band, from whom he hoped to obtain horses for their trek across the mountains. When Sacagawea arrived to serve as interpreter, she found the band was led by her older brother, Cameahwait, who had become chief on their father's death. Deeply moved by this reunion, Sacagawea might have taken advantage of such an astounding coincidence to return to her people, but instead she helped the explorers secure the horses they needed and journeyed on with them and her husband to the Pacific.

On the return journey, Sacagawea and Charbonneau parted with Lewis and Clark at a Hidatsa village on the upper Missouri, and from this point the historical record of their lives becomes somewhat conjectural.

Charbonneau evidently traveled to St. Louis at the invitation of William Clark, who had grown fond of the young Pompey and hoped he could induce his father to settle there. After a brief trial, however, Charbonneau returned to trapping, leaving his son in Clark's care. He worked for the American Fur Company, and later accompanied Prince Maximillian on the expedition that brought the artist Karl Bodmer to the upper Missouri in 1833.

Whether Sacagawea accompanied Charbonneau to St. Louis is uncertain. Some evidence indicates that she did make this journey, then returned to the upper Missouri with her husband where she died in an epidemic of "putrid fever" late in 1812. Other accounts say that Sacagawea ultimately rejoined the Shoshone on their Wind River reservation and died there in 1884.

<=*S=======<>+O+<>=====<^>====<<<+O+>>>====<^>=====<>+O+<>=======S*=>

(Matihehlogego)

Hollow Horn Bear, Brule/Sicangu Sioux, was born in Sheridan County, Nebraska in 1850. At age 16, he participated in Sioux raids against the Pawnee.

In the Red Cloud War of 1866-68, he led attacks against U.S. troops, first in Wyoming, then in Montana, and in 1869, against labor crews of the Union Pacific Railroad. After hostilities ceased, he was appointed Captain of Police at the Rosebud Agency, South Dakota, in which he had the duty to arrest Crow Dog for the murder of Spotted Tail.

He was chosen in 1889 to negotiate with General Crook and the U.S. Commission and acted as spokesman for his tribe. His picture was used on a U.S. 14-cent postage stamp, on a five-dollar silver certificate, and also on the reverse side of the buffalo nickel.

In 1905, he attended the presidential inauguration of Theodore Roosevelt, and in 1913, he led the Indian contingent in the inaugural parade of Woodrow Wilson. On his last visit to Washington, he caught pneumonia and died there.

<=*S=======<>+O+<>=====<^>====<<<+O+>>>====<^>=====<>+O+<>=======S*=>

~Native Pride Wisdom~

© 2001

<=*S=======<>+O+<>=====<^>====<<<+O+>>>====<^>=====<>+O+<>=======S*=>

Background Image:

"Gift of the Eagle Feather" by Howard Terpning, Jr.

Adapted to web background by Ani Bealaura

Copyright: 2001, All Rights Reserved

Divider Bars designed by Ani Bealaura

Copyright: 2001, All Rights Reserved

Full Moon Rising RC Complete Site Update Newsletter

Your comments and suggestions are welcome